Vocatives

Exploring how Zevy forms terms of address · 10 minute read · back to table of contents

Note: You can read this post with its original formatting over at the Zevy wordbook here, or you can read the inline version below.

The

vocative is a way of identifying the person whom one is speaking or writing to. In Zevy, there are two prefixes which are commonly used to do this:

- do- for the second person

- dese- for the first person plural

Here are some examples:

As seen from the examples, the pronunciation of the morpheme to which these prefixes attach is often reduced.

▾ How they're used ▾

Strictly speaking, these aren't simply vocative forms but are rather noun phrases that act as pronouns. By another name, we call them

pronominals.

As such, they can appear anywhere in a sentence:

if someone asks:

Deu mu, mata te at?

[ˈzeo m̩ ˈmatə ts a]

- Deu

- INT

- mu

- ABS,

- mata

- park

- te

- DAT

- at

- go

Who is going to the park?

one can reply:

Dovund mu at.

[ˈdovð m a]

- Dovund

- 2:friend

- mu

- ABS

- at

- go

You, friend, are going.

Dan ha me, dovund tedu rese mu mu moema.

[dã ˈha me ˈdovð tjed reze m̩ m̩ ’mojmə]

- Dan

- COMP

- ha

- RSMP

- me

- LOC

- dovund

- 2:friend

- tedu

- at house of

- rese

- arrive

- mu

- ABS

- mu

- ABS

- mo-ema

- IMP-say

Tell me when you get home, friend.

Vedesetritiis te make mu vemet hi me utnaka.

[ˈβedezetris ts̩ ˈmake m̩ βemeh ji me ˈhnakə]

- Ve-dese-tritiis

- NEG-1p-student

- te

- DAT

- make

- respect

- mu

- ABS

- ve-met

- NEG.AGR-put

- hi

- be.2

- me

- PRS

- utnaka

- teacher

The teacher doesn't respect us students.

▾ How they compare to third person forms ▾

Similar pronominals exist in the third person, formed using the following:

We won't go deeply into these in this post, but here are some quick examples:

one student asks:

Danaka ti zo hi me?

[ˈdanakə h zo j me]

- Da-naka

- that-teacher

- ti

- ABL

- zo

- see

- hi

- be.2

- me

- PRS

Do you see that teacher? [over there]

the other replies:

Det, utnaka mu, deu?

[ˈdeh ˈhnakə m̩ ˈzeo]

- Det

- yes

- ut-naka

- previous-teacher

- mu

- TOP

- deu

- INT

Yes, what about that teacher? [that you just mentioned]

the first continues:

Utnaka mu, nenaka temu hat: avaven!

[ˈhnakə m̩ ˈɲenakə tem̩ hah ˈwaβaβə]

- Ut-naka

- previous-teacher

- mu

- TOP

- ne-naka

- next-teacher

- temu

- above

- hat

- tall

- a-vaven

- 2POSS-father

That teacher is taller than this teacher [that I'm about to mention]: your dad!

the second replies:

Utnaka te det.

[ˈhnakə ts̩ deh]

- Ut-naka

- previous-teacher

- te

- DAT

- det

- good

Good for them.

The key takeaway here is that in Zevy, these types of prefixes prefixes extend so far as to be the most common way of referring to others. Among ordinary pronouns, only the first person singular

dit "me" is regularly used. Other simple pronouns exist, but generally speaking, referring to others using a simple pronoun is rude or overfamiliar unless you know them well.

▾ Their other extensions ▾

It turns out that

do- and

dese- can be used in several other ways. In fact, these prefixes are so overloaded that we're just might have to watch out for power failures as we explain all the work they have to do....

Jokes aside, here wo go!

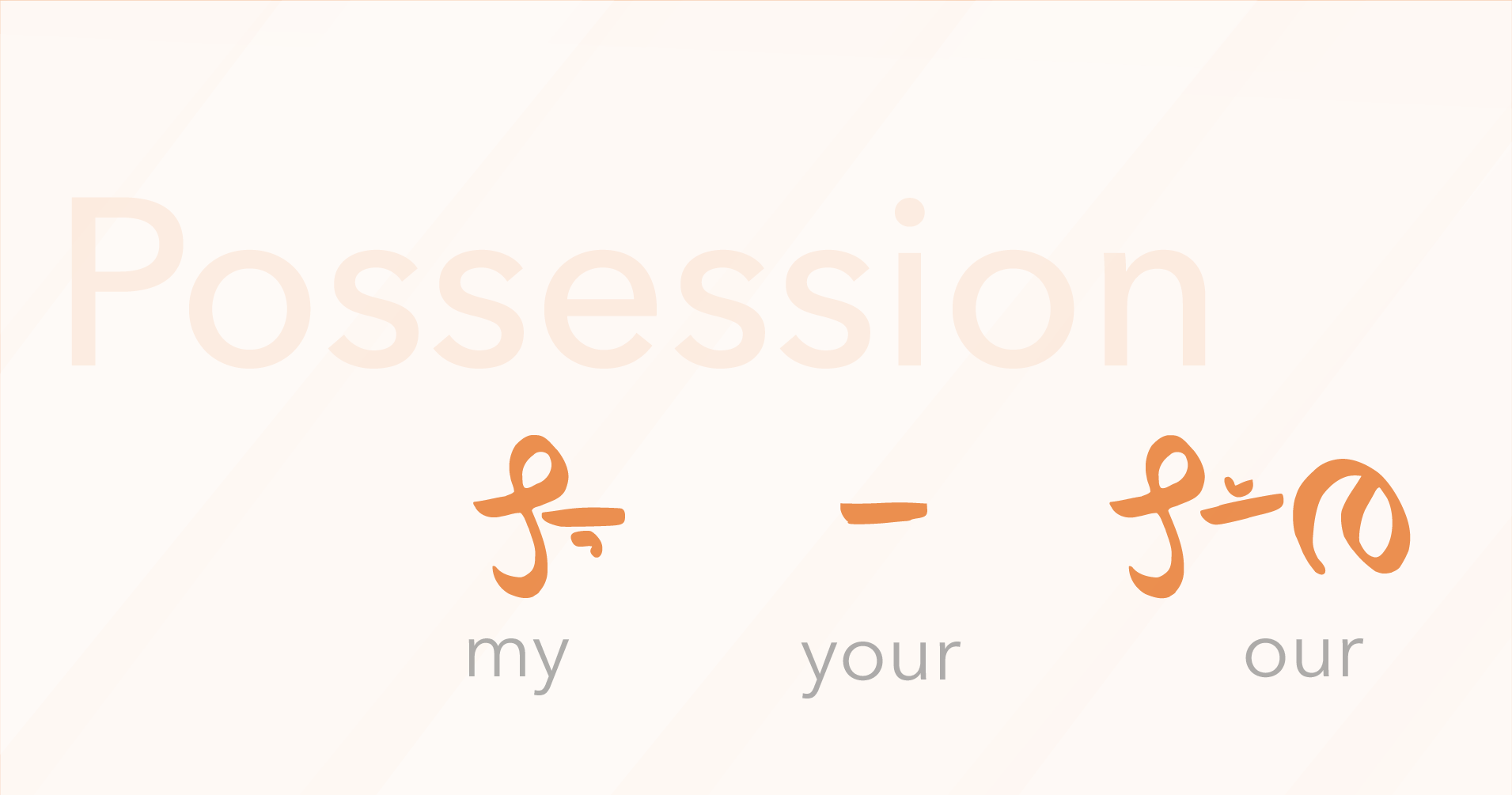

▾ The transient possessive ▾

In the notes on Possession, we talked about how Zevy expresses ownership; here, we revisit a variation of that. But to explain, let's go back in time and observe that the prefix

do- is actually derived from the demonstrative

do "this", which is the partner to

da "that". As such, the historical meaning of phrases like

dovund and

donaka is simply "this friend" and "this teacher". Only over time did they come to be used as second-person terms of address.

This semantic drift has lead to the following intermediate meaning which appears when

do- is used with inanimate objects. Here, the vocative interpretation makes little sense, as one would be unlikely to talk to an object. Instead, when used with inanimate objects,

do- refers to something that is either physically close to the listener, or logically associated with them. For example:

Doteva mu men hi det donaka?

[ˈdoteβə m̩ mẽ j deh ˈdonakə]

- Doteva

- 2-book

- mu

- ABS

- men

- give

- hi

- be.3

- det

- IMP

- do-naka

- 2-teacher

[Could you please] give me that book [near you], teacher?

Here comes the overlap with possesion: this usage of

do- can be translated as a second person possessive, "your", with the implication that the object is something that the addressee temporarily "owns" by virtue of being near it either spatially or temporally. So, the above example can also be translated as:

Doteva mu men hi det donaka?

[Could you please] give me your book, teacher?

This sense is distinct enough that it gets its own dictionary entry:

do (possessive). But if, by contrast, the possession is stronger, then one of the other constructions detailed in Possession must be used instead. For example, contrast the example above, "your book", with "your eyes" below:

Azoi mu ini hi det dotritiis.

[ˈwazəi m̩ jiɲi j deh ˈdotris]

- A-zoi

- 2POSS-sight

- mu

- ABS

- ini

- open

- hi

- be.3

- det

- IMP

- dotritiis

- 2-student

Open your eyes, student.

In this case, "eyes"

must be marked with the second person possessive prefix

a- rather than

do- because eyes are inalienably possessed.

▾ A note on politeness ▾

Note how in English, politeness is marked through indirection, using phrases like "Would you please." Those words don't appear in the original Zevy text. Instead, I've added them to the dynamic translation to reflect the politeness that Zevy conveys through other means.

First, intonation is critical: polite imperatives are coupled with the same rising intonation as questions, indicated in writing with the question mark. This parallels how English also uses questions rather than commands for politeness, though again Zevy has no additional auxiliaries.

Second, the choice of pronominal is crucial: the use of

donaka in the original Zevy sentence is the mandatory polite form of "you" in this sentence, even if an idiomatic English translation might also simply be

"Could you please give me that book near you?" in the context of a student speaking to a teacher. In phrases like these, the pronominal must be carefully selected to signal the speaker's stance towards the listener, and respect for the relationship between them.

▾ Vocatives vs. possession in the first person ▾

We saw above how in the second person,

do- blurs the line between vocatives, demonstratives, and possession. This doesn't occur in the first person, however, where the pronominal and the possessive are instead distinct.

Here,

dese- is strictly used for the pronominal, i.e.

"we X" or

"us X", while the related form

des- is used for the possessive,

"our X". These are derived from the same historical form, literally differing only in the addition or omission of an epethentic vowel. For example:

vocative:

Desetritiis mu tri hi det!

[ˈdezetris m̩ tri j deh]

- Dese-tritiis

- 1p-student

- mu

- ABS

- tri

- teach

- hi

- be.3

- det

- IMP

Teach us students!

vocative:

Destritiis mu tri hi det!

[ˈdestris m̩ tri j deh]

- Des-tritiis

- 1p.POSS-student

- mu

- ABS

- tri

- teach

- hi

- be.3

- det

- IMP

Teach our students!

▾ The temporal vocative ▾

Finally, there is one more neat way in which these prefixes can be used. Consider the following examples:

Desetesnei me dee.

[ˈdezetesɲəi me deje]

- Dese-tesnei

- 1p-patience

- me

- LOC

- dee

- stand

Stand in the patient us.

Doku me isi.

[ˈdoku me jiɕ]

- Do-ku

- 2-quiet

- me

- LOC

- isi

- sit

Sit in the quiet you.

These sentences show a very peculiar construction. What do they mean? The general formula is:

- then some noun or adjective

- then an auxiliary verb, either dee "stand" or isi "sit"

Put together, this conceptually means that the speaker is seen as entreating the listener (and in the first person plural, themself as well) to embody some quality. Then, the choice of auxiliary conveys how long the quality should be embodied. Choosing "stand" suggests that the quality is to embodied for a short period of time, while "sit" indicates a long period.

As a result, the examples above can be translated as follows:

Desetesnei me dee.

Stand in the patient us. → Let's be patient for a moment.

Doku me isi.

Sit in the quiet you. → Be quiet for a while.

And there you have it! A neat little construction that we refer to as the

temporal vocative because it attributes a state to the addressee for some period of time.

Note that the examples above are interpreted in the imperative even though there is no mood marker. This is the default, but not the only possibility, as the temporal vocative can be explicitly marked for other combinations of tense, aspect, and mood. For example:

Naka mu tri mu nes me, deseku me isi si te.

[ˈnakə m̩ tri m̩ nes me ˈdezeku me ˌjiɕi z tje]

- Naka

- teacher

- mu

- ABS

- tri

- teach

- mu

- ABS

- nes

- start

- me

- LOC,

- dese-ku

- 1p-quiet

- me

- LOC

- isi

- sit

- si

- be.1

- te

- FUT

When the teacher starts talking, we will be quiet for a while. literally → "We will sit in the quiet us."

There can even be multiple auxiliaries stacked on top of each other:

Dotesnei me dee ti isi hi me?

[ˈdotesɲei me deje h jiɕi j me]

- Do-tesnei

- 2-patience

- me

- LOC

- dee

- stand

- ti

- ABL

- isi

- sit

- hi

- be.3

- me

- PRS

Have you just been patient? literally → "Do you sit from standing in the patient you?"

Voila! Thanks for reading, you friends. Till next time

back to table of contents

back to table of contents