Re: If natlangs were conlangs

Posted: Fri Jun 21, 2019 11:50 am

Mesopotamia is well-known for having had frequent flooding historically in particular.

It's a big part of the reason why they have a civilisation. Flood control and irrigation were primary concerns of Mesopotamian polities, just as they were in early China (and arguably continue to be up to the present day).

The same is true of Ancient Egypt as well. (Building the pyramids is just what farmers did in their spare time.)

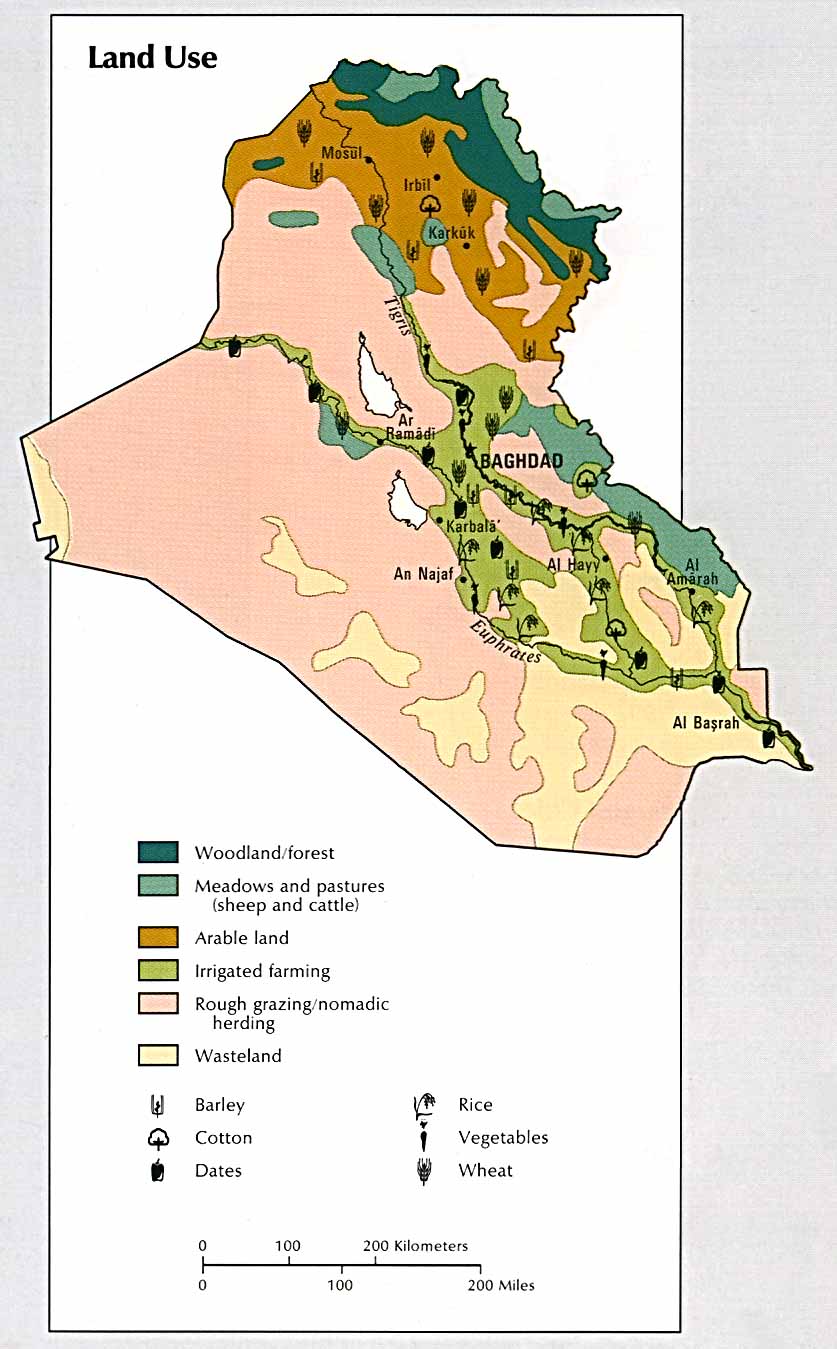

For both Akangka and malloc, this map of land use in Iraq may be useful.Akangka wrote: ↑Tue Jun 18, 2019 7:15 am Everywhere I see desert, I see a native culture utilizing agriculture. Even Atamaca desert. Isn't the point of desert is you can't easily grow a plant? The only place I see a culture without agriculture in desert is Australia and South Africa. Southwestern US is partial answer, because you can get both Apache and Pueblo in the same place. Gobi desert is also partial answer because people there is herding instead.

But that phoneme is so out of places, Why isn't English has another voiceless liquid?

Many linguists analyze this [ʍ] as a combination of two phonemes, /hw/. In any case, there is a similar consonant [ç] as in huge, which similarly results from a combination /hj/. The notion of "liquid" is fairly vague anyway; most resources I find consider /r/ and /l/ to be liquids, but not /w/ or /ʍ/.

Old English did have a series of /h/ + resonants, or voiceless resonants; /ʍ/ is the sole survivor. I suspect it's been stabilised by the alternations [xw] ~ [hw] ~ [ʍ]. Treating /hj/ as a consonant cluster misses the fact that the /j/ is strongly associated with the following vowel - treating the 'y' in 'Hyundai' as a consonant is a lost cause in English.Ryusenshi wrote: ↑Sun Jun 23, 2019 2:27 amMany linguists analyze this [ʍ] as a combination of two phonemes, /hw/. In any case, there is a similar consonant [ç] as in huge, which similarly results from a combination /hj/. The notion of "liquid" is fairly vague anyway; most resources I find consider /r/ and /l/ to be liquids, but not /w/ or /ʍ/.

bradrn wrote: ↑Thu Jul 04, 2019 12:53 amOh yes, I completely forgot about Saanich! That has to be the weirdest Latin-script orthography I know of! For those who aren’t acquainted with the sheer bizarreness (is that a word?) of Saanich orthography (a.k.a. SENĆOŦEN), here are some details:Whimemsz wrote: ↑Thu Jul 04, 2019 12:30 am That's a standard Salishan orthography; it only occurs in <t̓ᶿ> because there's no /tθ/ in the language, only /tθ’/. The Salishan language with the actually weird (aka stupid) orthography is Saanish (SENĆOŦEN), which (almost) only uses capital letters.

Resulting in the following easy-to-read text:

- All capital letters, except <-s> for some reason

- Stroked letters ȺȻꝀȽŦȾ (yes, T is stroked two different ways!)

- Comma for glottal stop (why? good question)

- Acute accent used with A/Á, C/Ć, K/Ḱ, S/Ś for no apparent reason (e.g. A and Á are the same, except the latter is used after post-velar consonants (what sort of language distinguishes palatal, pre- and postvelar?)) EDIT: palatal/pre/postvelar turns out to be the Americanist terminology for palatal/velar/uvular, which is indeed somewhat common.

(That weird triangle X thing should actually be X with line below.)SI,SI,OB BE₭OȻBIX̲ ,UQEȾ. ,ESZUW̲IL ELQE,. ,ESTOLX ELQE, ESDUQUD ,ESXEĆBID ȽṮUBEX̲ ELQE, ŚÍISȽ ,ÁL,ÁLŦ.

Oh, and according to Wikipedia, Saanich uses regular metathesis for aspect. All in all, it makes the rest of Salishan look positively sane… which is an impressive achievement. (I do wonder sometimes why Salishan got all the crazy stuff… extreme polysynthesis, weird orthography, nounlessness, occasional vowellessness…)

Well, it looks like there are actually three separate orthographies, all of which use period for the glottal stop! One orthography using it is bad enough, but how other people thought it was an idea good enough to copy is beyond me.

I don't see what's bad about that, it's easy to see and distinguish from punctuation marks, and looks like a glottal stop character.bradrn wrote: ↑Thu Jul 04, 2019 5:43 pmWell, it looks like there are actually three separate orthographies, all of which use period for the glottal stop! One orthography using it is bad enough, but how other people thought it was an idea good enough to copy is beyond me.

On the other hand, using a period is at least somewhat logical, unlike using a comma. I just wonder how they separate their sentences…

(Of course, then there’s Squamish, with its use of 7 for glottal stop. Let’s not talk about that one please.)

(I assume you’re talking about Squamish here.)

You can definitely see where the tones are, and what they are, but it’s a bit less direct than writing something like this:Wikipedia wrote: Bouч bouч ma dəŋƨ laзƃɯn couƅ miƨ cɯyouƨ, cinƅyenƨ cəuƽ genƨli bouчbouч biŋƨdəŋз. Gyɵŋƽ vunƨ miƨ liзsiŋ cəuƽ lieŋƨsim, ɯŋdaŋ daiƅ gyɵŋƽ de lumз beiчnueŋч ityieŋƅ.

At least it’s better than the current Zhuang orthography, though. When they got rid of the weird tone letters, they decided to copy Hmong and replace them with normal letters. So the current situation with both Hmong and Zhuang is that an arbitrary subset of letters represents tones, without any external indication of this except memorisation. So you get words like (in Zhuang) mwngz /mɯŋ˧˩/, hwnj /hɯn˥/, max /maː˦˨/ where the last letter represents a tone.Bou4 bou4 ma dəŋ2 la3ƃɯn cou6 mi2 cɯyou2, cin6yen2 cəu5 gen2li bou4bou4 biŋ2dəŋ3. Gyɵŋ5 vun2 mi2 li3siŋ cəu5 lieŋ2sim, ɯŋdaŋ dai6 gyɵŋ5 de lum3 bei4nueŋ4 ityieŋ6.

That's actually pretty awesome! Thanks for sharing that, I had never seen it. My first choice for tones is diacritics that match the tone contour, as in pinyin, but these would be a close second. Regular numerals stand out a lot. That's not entirely bad, as syllables are clearly separated, but I like the way the 1957 numerals fit in with normal letters.bradrn wrote: ↑Fri Jul 05, 2019 7:54 pm And if we’re talking about using numerals for tones, I have got to mention the Zhuang 1957 orthography. I’m not quite sure what happened there, but whoever created it may not have been entirely sane. See, they heard that numerals were a good way of representing tones, but they didn’t like the idea of mixing letters and numbers. So they — wait for it — made typographical variants of each number to use specifically as tone letters! That is, they used ƨзчƽƅ (capitals ƧЗЧƼƄ) instead of 23456. The effect is somewhat pretty:

You can definitely see where the tones are, and what they are, but it’s a bit less direct than writing something like this:Wikipedia wrote: Bouч bouч ma dəŋƨ laзƃɯn couƅ miƨ cɯyouƨ, cinƅyenƨ cəuƽ genƨli bouчbouч biŋƨdəŋз. Gyɵŋƽ vunƨ miƨ liзsiŋ cəuƽ lieŋƨsim, ɯŋdaŋ daiƅ gyɵŋƽ de lumз beiчnueŋч ityieŋƅ.Bou4 bou4 ma dəŋ2 la3ƃɯn couƅ mi2 cɯyou2, cinƅyen2 cəu5 gen2li bou4bou4 biŋ2dəŋ3. Gyɵŋ5 vun2 mi2 li3siŋ cəu5 lieŋ2sim, ɯŋdaŋ daiƅ gyɵŋ5 de lum3 bei4nueŋ4 ityieŋƅ.

You’re welcome! There’s a lot of strange romanization systems out there…

That pretty much sums up by feelings about this as well. I did originally try to include something like this statement in my post, but I couldn’t find a way to express it as concisely as you did.My first choice for tones is diacritics that match the tone contour, as in pinyin, but these would be a close second. Regular numerals stand out a lot. That's not entirely bad, as syllables are clearly separated, but I like the way the 1957 numerals fit in with normal letters.

As far as I know, Gwoyeu Romatzyh is the only system to use spelling-based tone indication. That’s probably a good thing — the world doesn’t need more of this madness…Wherever possible GR indicates tones 2, 3 and 4 by respelling the basic T1 form of the syllable, replacing a vowel with another having a similar sound (i with y, for example, or u with w). But this concise procedure cannot be applied in every case, since the syllable may not contain a suitable vowel for modification. In such cases a letter (r or h) is added or inserted instead. The precise rule to be followed in any specific case is determined by the rules given below.

[…]

A colour-coded rule of thumb is given below for each tone […] Each rule of thumb is then amplified by a comprehensive set of rules for that tone. These codes are used in the rules:

Pinyin equivalents are given in brackets after each set of examples. […]

- V = a vowel

- NV = a non-vowel (either a consonant or zero in the case of an initial vowel)

- ⇏ = "but avoid forming [the specified combination]"

Tone 1: basic form

* Initial sonorants (l-/m-/n-/r-): insert -h- as second letter. rheng, mha (rēng, mā)

* Otherwise use the basic form.

Tone 2: i/u → y/w; or add -r

* Initial sonorants: use basic form. reng, ma (réng, má)

* NVi → NVy ( + -i if final). chyng, chyan, yng, yan, pyi (qíng, qián, yíng, yán, pí)

* NVu → NVw ( + -u if final). chwan, wang, hwo, chwu (chuán, wáng, huó, chú)

* Otherwise add r to vowel or [[diphthong]]. charng, bair (cháng, bái)

Tone 3: i/u → e/o; or double vowel

* Vi or iV → Ve or eV (⇏ee). chean, bae, sheau (qiǎn, bǎi, xiǎo), but not gee

* Vu or uV → Vo or oV (⇏oo). doan, dao, shoei (duǎn, dǎo, shuǐ), but not hoo

* When both i and u can be found, only the first one changes, i.e. jeau, goai, sheu (jiǎo, guǎi, xǔ), not jeao, goae, sheo

* For basic forms starting with i-/u-, change the starting i-/u- to e-/o- and add initial y-/w-. yean, woo, yeu (yǎn, wǒ, yǔ)

* Otherwise double the (main) vowel. chiing, daa, geei, huoo, goou (qǐng, dǎ, gěi, huǒ, gǒu)

Tone 4: change/double final letter; or add -h

* Vi → Vy. day, suey (dài, suì)

* Vu → Vw (⇏iw). daw, gow (dào, gòu), but not chiw

* -n → -nn. duann (duàn)

* -l → -ll. ell (èr)

* -ng → -nq. binq (bìng)

* Otherwise add h. dah, chiuh, dih (dà, qù, dì)

* For basic forms starting with i-/u-, replace initial i-/u- with y-/w-, in addition to the necessary tonal change. yaw, wuh (yào, wù)

Though Mandarin is unusually suited to that approach, and really only if you think of its low tone in terms of the contour it gets when spoken in isolation. I mean, if you've just got a marked high tone, a macron is going to confuse a lot of people; and if you've just got marked high and low tones, the acute/grave system is probably as mnemonic as anything else you'd come up with. (Anyway it's won me over.)

Why do you think this is?

This is true. But tone sandhi makes everything more difficult, and I think using the isolated form simplifies the romanization. But if you really want to consider it as a low tone, it would be easy to just use a different diacritic like a̱ instead of ǎ, and write words like Pu̱tōnghuà, Guóyu̱, fùyo̱u, li̱xìng instead of Pǔtōnghuà, Guóyǔ, fùyǒu, lǐxìng. (I actually quite like this version, now that I’ve tried it out!)and really only if you think of its low tone in terms of the contour it gets when spoken in isolation.

This is of course true! I don’t think there’s any need to use the same diacritics for the same tones if they’re in different tone systems. Sort of like how you could use <ā>, <á>, <aa>, <a꞉> for /aː/, but often given the context only one or two choices make sense. (For more on this, see viewtopic.php?f=3&t=43&start=700#p15105 and the ensuing discussion.)I mean, if you've just got a marked high tone, a macron is going to confuse a lot of people; and if you've just got marked high and low tones, the acute/grave system is probably as mnemonic as anything else you'd come up with. (Anyway it's won me over.)