Subproject index

Episode 5: mean blue lady

Diary of Kaidan Žambey

17 reli 3422 (fidren)

Day 3: Dobray to Trežda

Nothing happened today, except for my almost missing cast-off. Nothing but feeling hungry, cramped and sad, and retching on using the barge latrine. I tried to sleep on the benches in the relative warmth of noon. Trežda is still in Krasnaya. We will pass into Verdúria tomorrow.

I alighted and got a limp zer and hard bed at the Mal Bardinó (where they haven't heard of Como). It was the only inn I could see on the sad waterfront. The sky was a sad mist, the water a sad mirror, the air a sad, cold, unwelcome bastard penetrating sad, tired, unwilling lungs.

While half my spirit was bleeding slowly into Išária the other half did tune up the dičura and do a few songs. There were kids at the inn, five of them, all little, who had ditched their sozzled families to play together. They came and watched while I caught the last grey rays and twanged away under the eaves, while the water dragged by in front of me. It was cold out, but it smelled better than inside.

“Gn. Ružë-Češa,” said the kid called Verek. “What are the pointy bits for?”

“They’re pegs to tune the strings with, Verek,” I said. He looked surprised that I knew his name, despite the fact they’d all been screaming it for twenty minutes playing

kašuek.

“Why has he got so many strings?” the kid called Danži whispered to Verek, setting them all off into shy giggles. I decided to do a little lesson.

“The big string is called Enäron,” I began.

“My daddy gives special presents to Enäron,” said Danži, confidently now.

“Mine too, mine too,” said the kid called Körka. “It’s called a sackwibice.”

“Well done, you two, Enäron is a god, so we sacrifice to him. He’s the biggest and most important god. Enäron is also the biggest and most important of our strings. All the other strings are named after other gods. Do any of you know any more gods?”

I was more than a little shocked by what they came up with. I had at my feet the children of cultists and perverts. And one Eleďe.

“Alright, alright! Erm, most of those gods don’t actually have strings of their own. Has anyone heard of Fidra?”

“She’s the mean blue lady who rules the night,” said Bunbul in a scary-story voice.

“Yes, Bunbul, well done. She’s to whom we dedicate our second most important string. Can you hear how they go together?”

I played F̣Ẹ, F̣Ė, F̣Ẹ̇ a few times.

“But isn’t Enäron’s wife Išira?”, said the Eleďe girl, whose name I hadn’t caught, and was a little older.

“Well done,

pavula, I guess you listen in school, eh. Well, the string names don’t really work like that. They’re in order like the months of the year, only, we start at Enäron, and sometimes we miss some of them out. And once we’ve been through them once we start again at Enäron… And Išira is actually the string below Fidra‒”

“Maybe Enäron and Fidra are more like special friends?” interrupted the Eleďe girl.

“Um. Well. They say… that once, Enäron and Řavcaena were… uh… special friends. And then Išira got… cross with Řavcaëna, so then‒”

“My mummy gets cross with my daddy’s special friends, too,” said Danži.

“Mine too! Mine too!” cried Körka and Verek, while the Eleďe girl nodded gravely.

At that I saw the man I had clocked as the father of (at least) Verek and Danži, an enormous man with arms the width of my head, striding across the the dock towards us. I thought it was probably time to end the lesson, and scuttled into the common room before I got an eyeful.

Alright, I guess not

nothing happened…

Notes:

zer ‒ pizza

Mal Bardinó ‒ Bad Coyote

Išária ‒ underworld

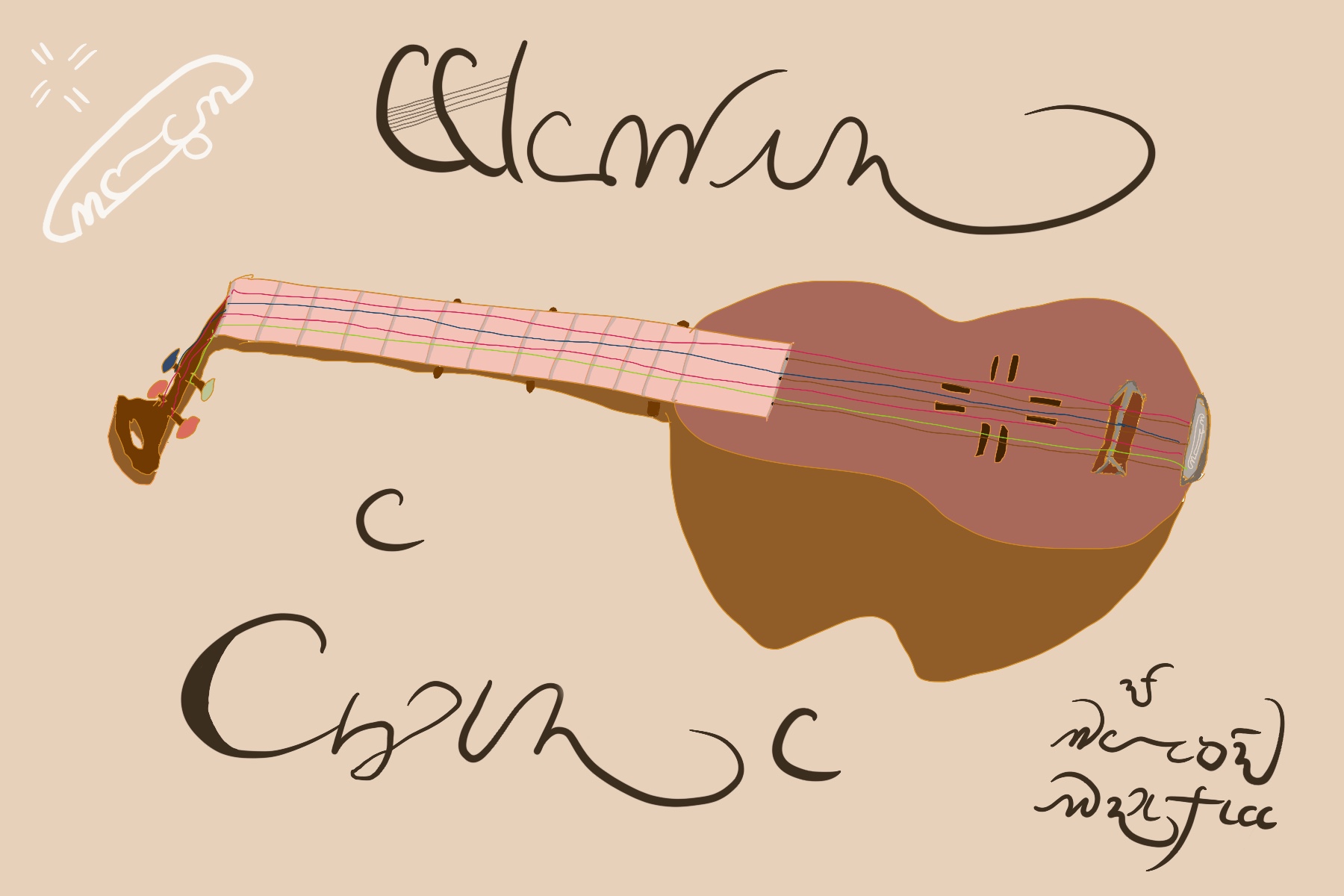

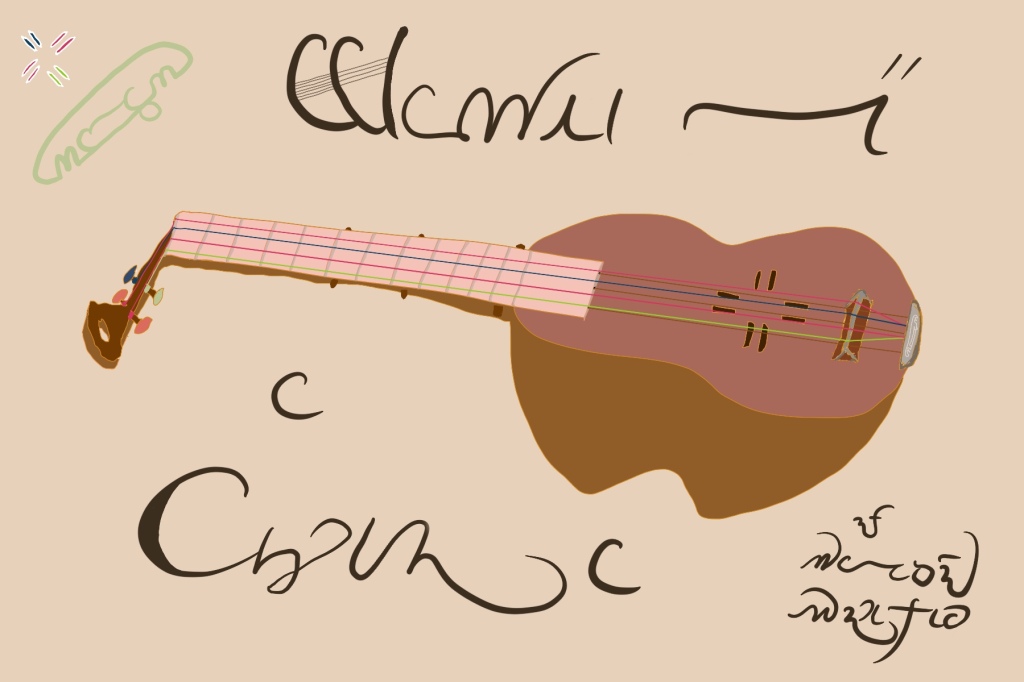

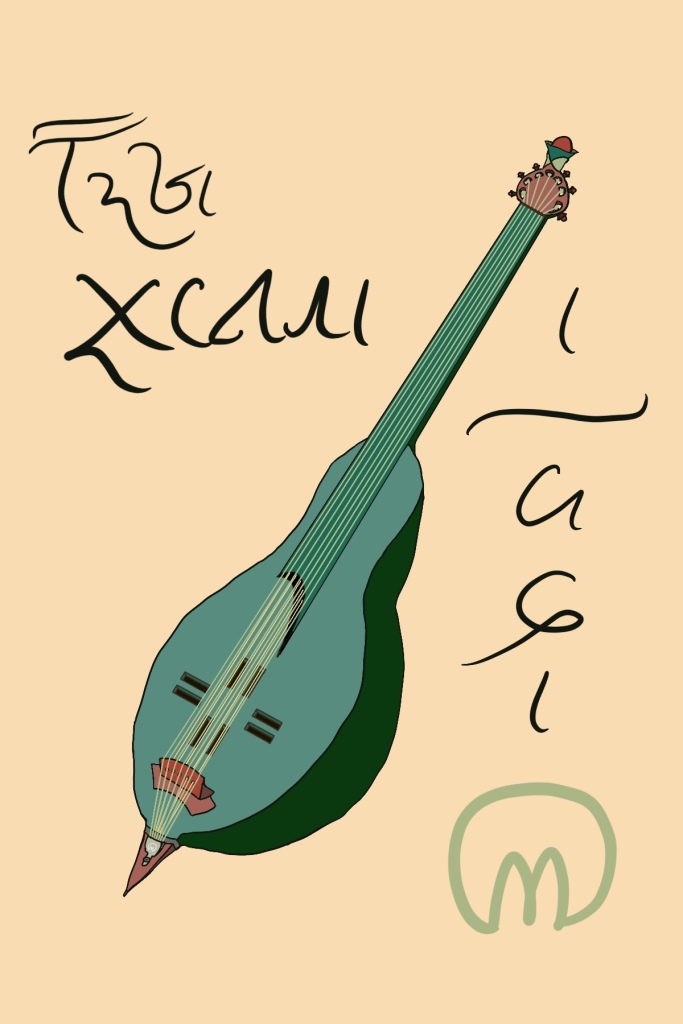

dičura ‒ zither. Evidently Kaidan has a chromatic zither, with 12 strings per octave. What he hasn’t remarked on is the slight angling of the strings: in each octave, five are strung angled up to the left, four to the right, and three are level (and set just a little higher than the others). The right side is for

embre (lit. ‘bitter, alkaline’) notes; the left side for

egre (lit. ‘sour, acidic, sharp’) notes; the level notes are

seor (lit. ‘clean, moral, pure’). Consequently there’s an area for playing the instrument diatonically (the right), an area to pick accidentals from (the left), and an area which highlights the strongest notes of the unison, fourth and fifth (the middle).*

Gn. Ružë-Češa ‒ Mr Red Case, after Kaidan’s red dičura case

kašuek ‒ hide and seek, lit. ‘hide yourself’

Edit ‒ originally the kids were boat passengers and this scene took place on board. On reflection I had imagined too many passengers on the barge, which largely draws cargo. So now they come from the inn. (Is it anachronistic that Kaidan learns their names this quickly? I think he is used to teaching small children, and he’s a people-watcher, so I reckon it’s just in his wheelhouse to notice what they’re called and how they interact.)

Note names

Since the Aďivro, Eretaldan note names have been standardised as (the vernacular reflexes of) the 12 chief Caďin gods, in essentially the same order that organises the calendar, though beginning at Enäron, rather than Řavcaëna. Note that Barakhûn also has a parallel set of note names for its decaphonic-derived system.

In the Aďivro, god names are often shortened with a dot beneath the first letter (with the exception of Escis, which uses the letter Ṣ).

This became standard practice to notate pitches. The system was extended so a dot above the abbreviation meant a note in an upper octave. This suited traditionally two-octave instruments such as the late-classical dičura and many of its modern reflexes, and the kaena. A dot both above and below means play the note in both octaves. (This system was later extended with more dots.)

The following table shows the sequence of note names in Caďinor and Verdurian, their notational abbreviation, their scale degree counting semitones from zero = tonic, and their rough terrestrial equivalents taking Enäron as (roughly) our note D.

|

Caďinor |

Verdurian |

Semitones |

Equivalent |

| Ẹ |

Endauron |

Enäron |

0 |

D |

| Ṿ |

Veharies |

Vlerë |

1 |

E♭ / D♯ |

| C̣ |

Caloteion |

Caloton |

2 |

E |

| Ḅ |

Boďnehais |

Boďneay |

3 |

F |

| Ọ |

Oronteion |

Oruseon |

4 |

F♯ / G♭ |

| Ạ |

Agireis |

Ažirei |

5 |

G |

| Ị |

Iscira |

Išira |

6 |

G♯ / A♭ |

| F̣ |

Fidora |

Fidra |

7 |

A |

| Ṃ |

Mieranac |

Mëranac |

8 |

B♭ / A♯ |

| Ṣ |

Escis |

Eši |

9 |

B |

| Ḳ |

Kravcaena |

Řavcaëna |

10 |

C |

| Ṇ |

Necťeruon |

Nečeron |

11 |

C♯ / D♭ |

Complications

Before the Aďivro, it had still been common practice to use god names for pitches. But which gods were used for which pitches varied considerably. Also, the Aďivro is our earliest complete evidence of a cyclical dodecaphonic system in use in Caďinor: previous documented traditions name fewer than 12 scale degrees. Or in one case, 36: six sets of six scale degrees, in a non-cyclical system somewhat reminiscent of an incomplete version of the Chinese Shi-er-lü. Pre-Aďivro music notation, whilst fairly plentiful, is thus notoriously difficult to interpret by non-specialists.

There are shortenings of the full note names, though there is local variation in this regard (TBC).

Kebri uses a compatible system with native nomenclature; the present system clearly post-dates the Aďivro, as its note names begin with the same letters, making Kebreni notation compatible (TBC). There have been attempts to ‘Eleďify’ the Verdurian system, including Erenáti proposals to rename notes after Eleďe saints, but these have not attracted widespread interest.

The Cuzeians had documented their division of the octave into 12 pitches nearly two thousand years prior, though they left no notated music. Cuzeian theorist Einatu implies that the Meťaiun used 6 or 7 notes, but had variants for each, which some scholars have interpreted as evidence of the Meťaiun originating the 12-note octave.

This system is a hybrid moveable-Do and fixed-Do system. I will say more about this later; for now I've chosen D to represent Enäron for two reasons: (a) what we call the Dorian mode (all the white keys of the piano from D-D) is one of the three foundational heptatonic modes of the Caďin system as set out in the Aďivro, so learning to think from D-D would marginally help you become more Almean in your music-making; (b) in the modern system,

cumpogul Enäron (‘absolute Enäron’) is fixed at 12^12 cycles per

piya, equivalent to about 564.93 Hz, which is between our D and C# (thanks to Mark for help with the calculations!).

Edit:

*If you’re looking for a major/minor equivalent, it

was to be found here, but after further work I

think I’m going to change a few things (including the colouring of the keyboard, to come) and disappoint/confuse you:

embre is now taken to mean ‘less pure than

seor, but less dissonant than

egre’. The Dorian (‘Svetle’) mode being foundational to this system, its notes are the seven

embre and

seor notes (including our minor third). The others are

egre ‒ including our major third. It may help to see

egre as describing citrus fruit (which can be both sweet and sour) ‒ and

embre as describing e.g. berries (again, can be sweet, though not in the same sharp-edged way as an orange, and sometimes bitter... this is attested ‒

embrezihe means ‘raspberry’). I’m going to try to let this idea settle ‒ it may go back to how it was before (e.g. the notes we call major are ‘egre’ and those we call minor are ‘embre’ ‒ though note that Eretaldan scales are not categorised in terms of their ‘major/minor’ profile).

Another note: this isn’t exactly a little instrument. Kaidan’s case is probably half the size of his pack and has to be carried next to it, awkwardly over his shoulder or on his front. It has around 30 strings (covering two and a bit octaves), weighs a good deal more than nothing would, is relatively fragile, and could have taken him a whole 20-minute

kašuek game to tune. It’s not enormously loud, either ‒ though it is strung with metal strings, has a well-crafted soundbox, and can carry better when picked with long fingernails or fingerpicks, played with beaters, and/or set on a bespoke frame (which, of course, Kaidan has not brought). It’s far from an ideal traveller’s instrument ‒ but he loves it, and it’s his best chance of making money, so here it is.