This thread is, or was originally, about understanding perfective aspect, so I was hoping that I might be able to contribute something on this subject. However, I don't think it's possible to understand aspect without understanding actionality, so I'm going to start with this subject.

Something about actionality

As mentioned above, I tend to think of the events or states construed by a linguistic expression as being somewhat separate both from the real or imagine world and from the linguistic expression itself.

The terminology for referring to the action construed by a linguistic expression is very disparate. Your can find terms such as

event, situation, eventuality, action, state-of-affairs, scenario, process among others used with a variety of meanings. I will mostly use my preferred terminology here, and sometimes give examples of terminological variation. If you want to read more about this subject, be aware that different authors use different terminology.

The

situation is the basic unit of action. This is more or less the action construed by a single verb constellation, with singular participants, and with no form of repetition, i.e. the action happens only once (see the

basic-level verb constellation of Smith 1997). However, there can still be singular situations with multiple participants or on multiple locations, perhaps because many participants act together in some way (collectively).

Situations can be classified into different types based on their

actionality. Actionality is actually my preferred to for what has been to referred to as Aktionsart earlier in this thread. Other terms for more or less the same basic idea are time schemata (Vendler 1957), lexical aspect, aspectual types (Croft 2012) and situation types (Smith 1997).

There are many different models of actionality. A common model, which I will more or less follow here, is to basically adapt Vendler's categories (Vendler 1957) and recognize three basic features:

dynamicity,

durativity and

telicity. Situations can then be divided into

states (static situations) and

events (dynamic situations). Events can be further divided into

activities (durative and atelic),

accomplishments (durative and telic) and

achievements (punctual and telic). Whether punctual events can be atelic or not kind of depends on your definitions of telicity, but some authors recognize

semelfactives as a distinct separate type (Comrie 1976, Smith 1997). States are typically durative but

point states ("It is 5 o’clock", "The sun is at its zenith") have also been recognized (see Croft 2012 p. 43, citing Mittwoch 1988). Some interesting overviews of different classifications are found in Christensen (1995) and Croft (2012).

Situations can have internal structure and involve a repetition of

phases (see Cusic 1981). This is probably not that important for understanding aspect.

Situations can also be repeated themselves. Multiple situations may be repeated on one

occasion, where they are in some way connected to each other. Situations may also be repeated over multiple occasions (again, see Cusic 1981). It is actually possible to introduce even more levels of repetition ("I used to eat two bags of candy every thursday of every other week of every other month of every third year"). It may also be necessary to distinguish

habituality from other forms of repetition.

I use the term

scenario to refer to the entirety of action. This is not a widely used term, and it doesn't seem to be that common to use a special term to distinguish the totality of action from a single situation (Cusic 1981 has the term "history", Hollenbaugh 2021 seems to use the term "eventuality").

It is very important to recognize that repetition can change the actionality of the scenario (see Smith 1997 ch. 2.1). "I knocked once at the door" construes a punctual scenario but "I knocked at the door for two hours" construes a durative scenario involving a repetition of punctual situations. "I ate up a bag of candy" construes a telic situation but "I ate up a bag of candy every day" construes an atelic scenario involving the repetition of telic situations.

Something about aspect systems

The term

aspect is unfortunately used with a variety of meanings. The type of aspect that this thread is mostly about is what Smith (1997, especially ch. 4) refers to as

viewpoint aspect. She describes viewpoint aspect as functioning like a camera to make the scenario (or situation in her words) visible to the receiver. Note that while explicit marking of actionality can frequently operate on the level of the situation (cf English "I ate

up a bag of candy every day"), I think viewpoint aspect tend to operate on the level of the scenario. This is probably not without exceptions, though.

Now, we should recognize that even if the same label is used for some aspect found in different languages, there is obviously going to be differences between how they are used. I think we may broadly be able to recoginize the following idealized systems, but I do not claim that any language exactly follows any of these idealized systems and there may well be further types:

- Slavic-style perfective–imperfective, which is very sensitive to actionality. Punctual scenarios require the perfective (but note that repeated punctual events make a durative scenario). Durative atelic scenarios require the imperfective. Durative telic scenarios can take either the imperfective or the perfective. Static and habitual scenarios typically require the imperfective (since they are atelic and durative).

- Romance-style perfective–imperfective (or aorist–imperfect), which is less sensitive to actionality, although punctual scenarios still require the perfective. However, durative scenarios can take either aspects regardless of telicity, and this also includes static and habitual scenarios.

- English-style simple–progressive, which is very similar to Romance-style aspect, but static and habitual scenarios don't take the progressive.

The distinction between Romance-style and Slavic-style aspect is due to Dahl (1985). This is not a claim that Slavic or Romance languages have ideal Slavic-style or Romance-style aspect systems, and English probably doesn’t have an ideal English-style system either. From what I understand, the Russian aspect system is among the most Slavic-style, while I think Western Slavic languages may have more Romance-style characteristics. Some Slavic languages, most notably Bulgarian, have been claimed to combine both systems in the past tense (Lindstedt 1995), so that both Slavic-style perfective and imperfective verbs can be used with the imperfect (Romance-style past imperfective) and aorist (Romance-style past perfective) for a four-way contrast.

While I claimed above that in the ideal Romance-style system, static and habitual scenarios can take either perfective or imperfective aspect, some languages may require the imperfective here. There could also be some kind of dedicated stative or habitual marking.

Despite the cross-linguistic differences, the similarities between different perfectives (and the English style "simple") and imperfectives (or progressives) should be recognized.

Approaches to viewpoint aspect

As mentioned above, languages may require a specific viewpoint aspect for some actional types. But there are often some types of scenarios that can take more than one aspect, with some difference in meaning. So what is this difference? There are many approaches to this question.

One common approach to viewpoint aspect is to say that "the perfective looks at the situation from outside, without necessarily distinguishing any of the internal structure of the situation, whereas the imperfective looks at the situation from inside, and as such is crucially concerned with the internal structure of the situation" (Comrie 1976: 4). Dahl (1985: 74) calls this

the 'totality' view of perfectivity. This view was mentioned by bradrn in the initial post of the thread, and I tend to agree that it's a bit hard to understand what this means in practice.

Below, I will instead present my favourite approach to viewpoint aspect – which from what I was able to tell is missing from this thread. There are nevertheless other approaches which are also interesting and worth checking out, see for example Smith (1997) and Johanson (2000). A honourable mention goes to the chronogenetic approach of for example Hewson & Bubenik (1997) and Hewson (2012), among other works by especially Hewson, although the approach goes back to Gustave Guillaume. I honestly don't think I understand this approach, especially its distinction between ascending and descending time, but I nevertheless find it fascinating.

One approach

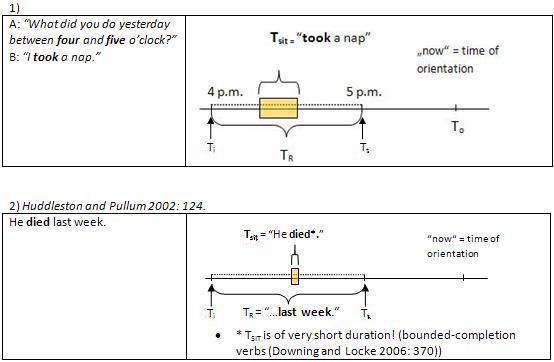

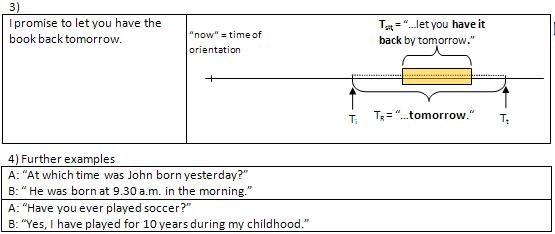

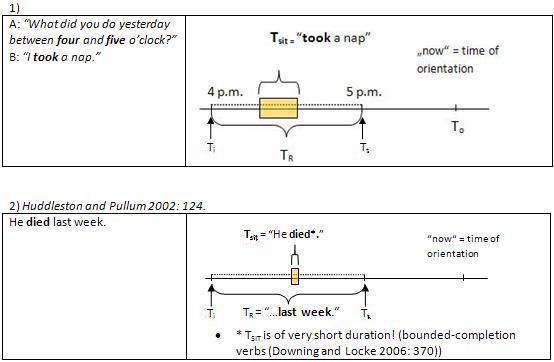

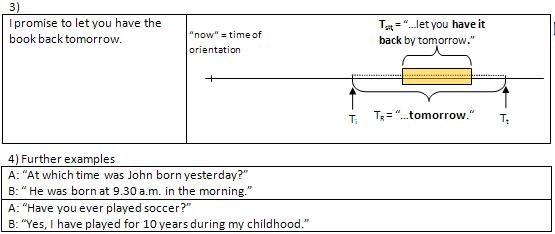

Another very common approach, and also the one that I find the most enlightening, is to see viewpoint aspect as the relationship between some different time intervals. If I'm not mistaken, this is what is often called the Neo-Reichenbachian Model, following Klein (1994), but adopted from Reichenbach (1947). Let's first define the following:

- Ts: Scenario time, the time from and including the start of the scenario up to and including the end of the scenario. Huddleston (2002) calls this the time of situation or Tsit. It can also be called eventuality time, event time or E.

- Tr: Reference time, which is basically the viewpoint of the viewpoint aspect. This can be a single point in time or a duration of time. The reference time can be explicitly marked for example by a time adverb ("I ate some candies yesterday") or an adverbial clause ("I was eating some candies when he arrived"). The reference time of an answer might follow from a question (Q: "What were you doing when he arrived?" A: "I was eating some candies!"). However, the reference time is not always explicit. Huddleston (2002) uses the term time referred to or Tr. It is also frequently labelled simply as R. The terms topic time, TT, or assertion time, TA are also used (see Hollenbaugh 2021: 54 ff).

- To or Td: Orientation time or deictic time. This is a point in time which is typically the time of the utterance, and for simplicity, we should assume that this is the case and only use the term orientation time or To. But see Huddleston (2002: 125 ff) for instances where this is not the case, and for the distinction between To and Td. Terms such as utterance time Tu, speech time, speech event time, Ts or S, and origo, evaluation time or perspective time are also used (and distinguished), alongside O and T0 (Hollenbaugh 2021: 54 ff).

With this approach, absolute tense marks the relationship between the reference time and the orientation time. The past tense marks that the reference time is anterior to the orientation time (T

r < T

o), the present that the reference time is simultaneous with the orientation time (T

r ⊇ T

o) and the future that the reference time is posterior to the orientation time (T

r > T

o).

Viewpoint aspect (and relative tense) mark the relationship between the scenario time and the reference time. Basically, the perfective aspect is used if if scenario time is entirely contained within the reference time (T

s ⊆ T

r), or at least if the endpoint of the scenario time is contained within it. If instead, the reference time is contained within the scenario time (T

s ⊇ T

r), the imperfective (or progressive) aspect is used. Languages may differ in how they treat scenario times that are equal to the reference time (T

s = T

r, see Hollenbaugh 2021: 68 ff and Gvozdanović 2012: 795). An anterior relative tense may be used when the scenario time is anterior to the reference time (T

s < T

r) while a posterior relative tense may be used then the scenario time is posterior to the reference time (T

s > T

r). The model can also be expanded to include the perfect/restrospective and prospective aspects.

The following illustrations from Glottopedia may be helpful (T

sit is my T

s):

Under this approach, it may also be said that the Slavic-style perfective requires not only that the reference time contains the scenario time, but also that the endpoint of the scenario time is

material rather than simply

temporal (cf. Lindstedt 1995). In other words, the scenario has to be telic, and when the scenario ends (within the reference time), it should have reached its telos and thus be finished rather than simply stopped. With a Romance-style perfective or English-style "simple", a temporal endpoint is sufficient.

For examples of this approach, see Klein (1994), Huddleston (2002), Gvozdanović (2012), and Hollenbaugh (2021).

References

- Christensen, Lisa (1995) Svenskans aktionsarter: En analys med särskild inriktning på förhållandet mellan aktionsarten och presensformens temporala referens

- Comrie, Bernard (1976) Aspect: An Introduction to the Study of Verbal Aspect and Related Problems

- Croft, William (2012) Verbs: Aspect and Causal Structure

- Cusic, David Dowell (1981) Verbal Plurality and Aspect (Dissertation)

- Dahl, Östen (1985) Tense and Aspect Systems (read here)

- Glottopedia, the articles on Aspect and Perfective.

- Gvozdanović, Jadranka (2012) Perfective and imperfective aspect, in Binnick, Robert I., The Oxford Handbook of Tense and Aspect (chapter 27)

- Hollenbaugh, Ian Benjamin (2021) Tense and aspect in Indo-European: A usage-based approach to the verbal systems of the Rigveda and Homer (read here

- Huddleston, Rodney (2002) The verb, in Huddleston, Rodney & Pullum, Geoffrey K. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language

- Johanson, Lars (2000) Viewpoint operators in European languages, in Dahl, Östen, Tense and Aspect in the Languages of Europe

- Klein, Wolfgang (1994) Time in Language

- Lindstedt, Jouko (1995) Understanding perfectivity - understanding bounds (read here), in P M Bertinetto, V Bianchi , Ö Dahl & M Squartini (eds), Temporal reference, aspect and actionality

- Hewson, John & Bubenik, Vit (1997) Tense and Aspect in Indo-European Languages: Theory, Typology, Diachrony

- Hewson, John (2012) Tense, in Binnick, Robert I., The Oxford Handbook of Tense and Aspect (chapter 17)

- Mittwoch, Anita (1988) Aspects of English aspect: on the interaction of perfect, progressive and durational phrases. Linguistics and Philosophy 11:203–54

- Reichenbach, Hans (1947) Elements of Symbolic Logic

- Smith, Carlota S. (1997) The Parameter of Aspect, second edition (first edition published in 1991)

- Vendler, Zeno (1957) Verbs and Times, in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 66, No. 2. (Apr., 1957), pp. 143-160 (read here), also reproduced with only minor changes in Vendler, Zeno (1967) Linguistics in Philosogy (read here)