So, History Part 1:

Historical Outline

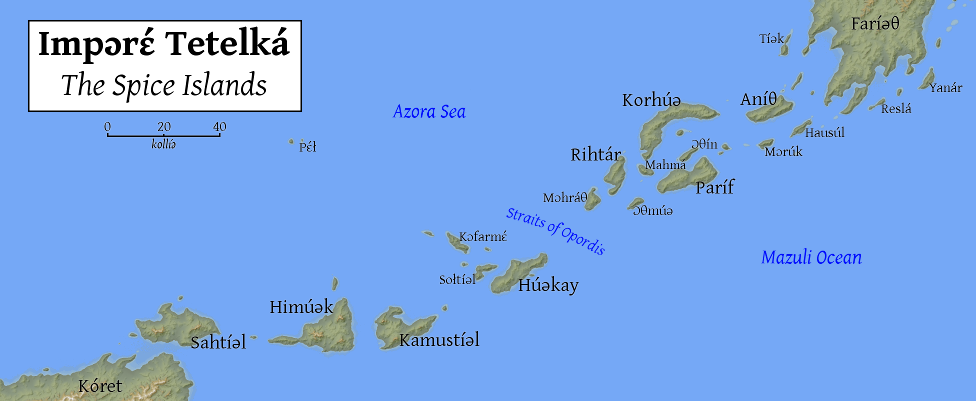

Note on names: I'm not going to be consistent here. I'm going to be using the modern names for the Islands: thus Korhúǝ for Corsoua etc; but for the wider world I'll either be using the standard Tailancan-derived terms I normally use or the native names as I see fit. The reason for this, extratextually and for example, is because while the Tailancans referred to the mysterious Qîrian civilisation as toi Cūreiai, I've always used Qîr in my own notes. However, to save myself the headache of leeward/windward (as pointed out above!), I'm going to adopt the Telpahké terms Somíl 'west' and Sórtay 'east' respectively for the two groups of islands. They also mean 'rainy season' and 'dry season' respectively, the shift being from the season to denoting the direction from which the summer and winter monsoon winds originate.

Note on dating: there is no one established calendar in Adeia or Rascana, let alone the Spice Islands. Virtually every state or religion has its own way of recording years, none of which is intuitive. As a result, scholars in the western half of Adeia have long used the 'Count of Helignatos', which takes the accession date of the first king of Tailanis as an easy way to keep track of years in annals and the like: the current year is 1632, and this is the count I use below.

It should be noted however that this calendar has no use in everyday life by any culture in the civilised world. If you ask a Carastan for the current year he will say 'the 271st year in the reign of Gesostinos IX the Perplexed', while a Tagorese merchant from Yɛṃ Tǝlar will respond that it's 'year three in the seventh indiction of Mbrɔḥ Cɛṃ'. In the Spice Islands themselves, the Somíl Islands generally use variations on the Tariññese 'spoke and wheel' count, in which the current year would be 'the third lion (year) of the seventh wheel'. Each state in the Sórtay Islands used to name each year according to the ruling archons at the time, which still holds true for most internal matters. However, it is more common to number years since the Treaty of the Forests (see below)- under which count the current year is 319.

Before beginning, a few general observations and a couple of caveats. Insular history is, largely, anything but insular. The Spice Islands are not an isolated archipelago forming a unit closed against the outside world: they are at the crossroads between the two civilised continents and have always been directly adjacent to some of the most advanced cultures on Telmona. They are the (sole) source of incredibly valuable commodities, which has always attracted outside interest. Therefore, it's not really possible to make much sense of Insular history without reference to the rest of the world. To even cursorily discuss the history of the Spice Islands without talking about the Phareitans, the Tailancan-Chadati wars or the rise and fall of the civilisations of the Mafreti peninsula is like trying to talk about the history of Italy without referring to the rest of Europe. But to just talk about any of the above without any context turns the whole thing into a slew of impenetrable names. As such, I've included a map and a very quick and dirty guide to the peoples and cultures mentioned in the main text. I've also called it a prolegomenon because I'm pretentious like that.

Another thing to remember is that given the geography of the islands, this isn't a nice neat story about the rise and fall of empires and kingdoms. Nobody has ever been able to politically unify the Telpahké-speaking world; in fact it's only the much smaller islands that have ever had a single government. I've tried to limit myself to noting trends in political history rather than going into much detail: this shouldn't be taken as an indication that history is just something that happens

to the Islands, but rather that the individual struggles of (say) Meleθɔ́ and Partíǝk - long-standing rival city-states on the island of Paríf - are just too detailed and complex to go into in any detail. Just remember that under the surface of the account below tribes, city-states and other various polities are busy jockeying for power, intriguiging and fighting amongst themselves pretty much constantly.

Prolegomenon to Insular History (or: a quick and dirty guide to the places and people of the civilised world)

Below is a map of the continent of Adeia and the northern part of Rascana, with the main relevant regions highlighted and labelled. Rather than going through even a brief summary of the grand sweep of Adeian history, I'll just quickly outline each area and how it's significant.

Cureia

Cureia

This was the first region of Telmona to develop agriculture: primarily a package based on wheat and barley and heavily dependent on irrigation from the Wanti river system. The first urbanised society originated here: that of the Qîr, who we can also thank for inventing writing first.

The Mafreti Peninsula

One of the first areas to acquire writing, urbanism and agriculture from the Qîr. The peninsula is bisected east-west by the Athros mountains, with the western half being rather less rugged. The main civilisation here in antiquity was that of the Achaunese, who were among the first to engage in long-distance seaborne trade. They also were instrumental in exporting civilisation to:

Mailona

The main area of focus here is the eastern part of the subcontinent, which is the homeland of the Lacarans. The Lacarans have organised themselves into four successive empires: the first three being based around Tailanis, the most recent around the city of Carasta. Major importance to early trade networks was the production of silk.

Chadatar

Is primarily steppe, but is indented with two significant river valleys. The dominant peoples here were initially the nomadic Daŋhai and then the related Chadati. The Daŋhai conquered the Wanti valley in the fifth century, and were conquered in their turn by the Chadati in the eighth. The Chadati went on to conquer both the second Tailancan Empire and the states of Taxaria before collapsing in the Crisis of the Tenth Century.

Taxaria

Taxaria doesn't get involved much in the story of the Spice Islands directly, but has always been a major motor of transcontinental trade. The great silver mines of Kɨṅgrao financed the insatiable Tagorese appetite for western silks, slaves and spices until the money ran out in the twelth century, precipitating the first international financial crisis.

Rascana

From an Adeian point of view, Rascana is a mysterious and exotic locale. However, the people there developed agriculture not long after the Qîrians, which would have important results for the Spice Islands. Historically, the major players have been the Tariññese, who dominate the northern half of the continent, whose history is a cycle of empires forming, splitting and then forming again.

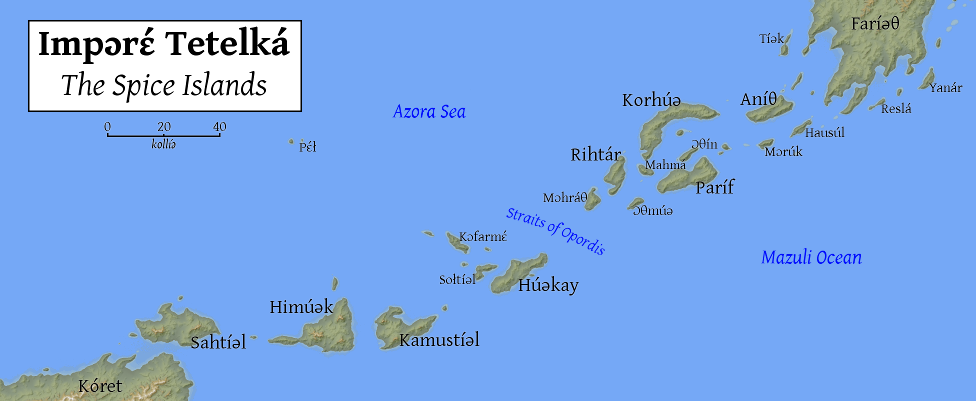

For ease of reference, I've included the map of the islands again below, to save people having to scroll up to the first post to work out exactly where (say) Tíǝk is.

Prehistory: -5000 to -500

Prehistory: -5000 to -500

While archaeology provides evidence of humans traversing and visiting the Spice Islands since at least the end of the last glacial maximum, the first firm evidence of permanent settlement we have is from approximately six and a half millenia ago. These settlers from the Adeian mainland were clearly early agriculturalists, with pottery working, domesticated dogs and goats and a crop package incorporating wheat and barley. Based on their artifacts, we can confidently state that they originated on the east coast of the Mafreti peninsula, and initial settlement was on the northernmost of the Sóntay Islands.

However, these early settlers did not remain their initial settled agricultural way of life for long. Cereal crops adapted to the more arid conditions of Cureia do not thrive in the much wetter climate of the Spice Islands, and the feeding habits of goats are particularly unhelpful to delicate insular ecosystems. By at least -4000 agriculture had been entirely abandoned and the population of the Sóntay Islands had reverted to a hunter-gatherer economy. Their population density remained low, and their technology remained relatively 'primitive', losing pottery and even textile manufacture. They had simple dugout canoes and the limit of their settlement appears to have been the Straits of Opordis. Based on obsidian finds throughout the Sóntay Islands, it is clear that they made the journey to Himúǝk, but no permanent to settlements appear to have been made.

A couple of millennia later, the inhabitants of the north-eastern coast of Rascana had developed something which would revolutionise the islands: the outrigger canoe, which enables simple canoes to be safely paddled much greater distances than the simple dugouts previously used. Equipped with a fairly complex agricultural package already well-adapted to the tropics (including the domesticated Rascana junglefowl), the canoe people exploded into the Somíl Islands. These people spoke a Atzato-Tarian language, directly ancestral to modern Telpahké.

By about -1500, the Somíl Islands were populated by settled agriculturalists (although horticulturalists might be a better term here), organised into simple tribal-based structures and engaging in a lively trade for obsidian, jade and feathers across the shallow inter-island seas. On the other hand, the Sóntay Islands remained populated by hunter-gatherers at a very low population density, whose main interaction with the Somíl people was a mixture of trading for obsidian and being the subject of repeated slave raids.

At about the same time, the cultures of Adeia had coalesced into the first states, with hierarchical structures and command economies. Non-labouring elites are quick to develop a taste for luxury goods, and the first polities to take advantage of this were the Achaunese-speaking city states of the western Mafreti peninsula. The

ṭarūnī 'kings' of these states sent out square-rigged sailing ships, north to the emerging urban civilisations of Mailona to acquire silk and south to the Sóntay Islands for slaves, exotic feathers and (importantly for the tree-poor Mafret) wood. These they would exchange for precious stones and metals in the recently united Qîrian sphere, and became rich in the process.

Around -900 or thereabouts, we see the development of dry rice agriculture in the uplands of Korhúǝ and Aníθ, allowing the Sóntay islanders to develop rather more dense settlements. This would have significant consequences later on.

Red Wings of Death and beyond: -500 to 253

The fifth century before Helignatos was a time of utter disaster for the civilised peoples of Adeia, and almost led to the total collapse of Adeian civilisation. The Atzato-Tarian speakers of the Somíl Islands, whom we can now refer to as the Impar, had not a small hand in this.

To put the disaster into a wider context, this had been on the cards for quite a while. The most advanced culture on the planet since its discovery of agriculture had been based in Cureia. Intensive irrigation-based agriculture supported an immense population density for the time, and facilitated a highly centralised, stratified society hungry for luxuries. Arranged around Cureia like planets around a star were the civilisations of Mailona and the Mafreti peninsula, all feeding the beast with goods and luxuries and receiving the benefits of civilisation in return.

However, almost two millenia of intensive irrigation has its consequences: soil salinity in the valley of the Wanti, the Cureian heartland, had increased to the point that vast swathes of formerly productive agricultural land became little more than deserts. In the Mafreti peninsula, the increasing size of Achaunese navies had denuded the slopes of the Athros Mountains of their trees, leading to disastrous erosion. On top of this, global cooling reduced the seasonal rains and led to widespread drought.

The Spice Islands were not immune to the collapse of the outside world. The failure of the monsoon severely impacted on the dry rice-based agriculture of the Sóntay Islands, and the cessation of trade with the Achaunese led to widespread unrest and collapse of societies based on the redistribution of this foreign wealth. More serious, however, were the events taking place on the north coast of Rascana.

Urbanism had been on the rise in northern Rascana for the past millenium, with an increasingly complex society to go with it. More animals were domesticated, food production became more efficient, and population densities rose. Given the endemic warfare between the various groups, people clustered more and more into centralised protected sites: the first cities of Rascana. And more and more germs were passed around.

The plague began in Rascana and swiftly spread to the Impar. The impact on the Impar was severe enough to cause widespread panic; and triggered their expansion out of the Somíl Islands into the Sontáy Islands, devastating the already weakened native population and quickly spreading the plague to the ravaged Achaunese. The fragmentary Adeian records of the time suggest that the plague was an influenza-like epidemic; and terrifyingly it killed not the elderly and infirm or children, but rather healthy young adults. Insular records of the plague are largely non-existant, but part of the

Song of Thunder, part of the traditional rite which opens the rainy season may preserve some folk memory of this time:

Tehnɛ́ θoké támaθ fefré Impár

somelɛ́ solɛ́ lamparé mar.

Tehká sɔtólok ko tehká entíǝ!

Tehká kóko ko tehká ɔmaθíǝ!

Impɔrɛ́ mitá Pɔhrákoy.

The People fly on red wings of death,

before the black clouds of the west.

Warriors die, elders do not die!

Maidens die, mothers do not die!

The Pɔhrákoy stalks the people.

(A

pɔhrákoy is one of the mythological hybrid animals of which the Impar are so fond. In this case, it has the body of a python, the wings of an eagle and the head of a tiger. It occupies a place in Impar thought somewhere between a Fury and a more benign psychopomp.)

The plague eventually burnt itself out, and the Impar found themselves in possession of not only the whole archipelago but also a agricultual package which was well suited to the drier Sontáy Islands. Dispossessing the aborigines of their land and either keeping them as slaves or driving them off into the forests, the Impar swiftly settled down to farm and bicker. When the climate finally reached an equilibrium again and the monsoon returned on a predictable basis, the Impar found that their flooded rice fields produced a much greater surplus than the well-drained ones. And so wet rice cultivation began, prompting something of a population explosion.

(A quick ethnographic note: Telmonan humans do not have quite the same range of phenotypes as Terrestrial humans do: everyone's pretty much a shade of brown. However, the Impar and the natives of Rascana have noticeably darker skin than Adeians do- approximately the difference between (say) southern Indians and Middle Easterners. The displaced natives ended up as hunter-gatherers again in the forests in the interior of the islands where as

sokór, they gave rise to tales of the little pale men of the forests.)

Offstage, the civilisations of Adeia began to recover from the collapse. Gone were the large, centralised empires of the Qîr: the main powers now were the city-states of the Achaunese. As elites are wont to do, the elites of the Achaunese began to crave luxuries and so international trade recommenced. Previously, the main products of the islands had been limited to feathers, obsidian and slaves; however, when Achaunese merchants returned to the archipelago they found not docile semi-nomadic horticulturalists who were easily fleeced with a handful of amber beads, but rather a sophisticated and settled society who desired more than just trinkets, and had more to offer than just feathers and rocks.

By about -100, a lively trade between the Achaunese and the Impar had developed. In return for Mailonan silks and iron from the Athros mountains, the Impar offered fish, rice, pearls and, most importantly, spices. The Achaunese for their part established trading colonies called

mablaʔī, which survives as the Telpahké word

mɔhláy 'market'. Achaunese sailing technology is adapted and combined with native outrigger technology, improving the ability of Impar leaders to project their power beyond their own shores. The influx of wealth from the north and the improvements to agriculture led to an increasingly hierarchical society, with the native chiefs aping Achaunese ways. The original Telpahké word for 'chief' was, at this stage, something like *

kʰāwa (cognate to the Tarì

khāva 'landowner'). However, it was displaced by the Achaunese loanword

paynūn 'judge', the title given to the administrators of the trading colonies: this gave rise to the modern Telpahké word for 'king' is

fainú. (While we're at it, the Achaunese autonym

ʔAqāwunu gives the modern Telpahké

ahkúǝ 'merchant'.)

Of course, all good things must come to an end and Achaunese civilisation ended with a crashing fall in the year 253. Things had been questionable for a while: internecine strife between the Pandayi and Mayriqi leagues through the late first century ended with a Mayriqi victory in 98, but was swiftly followed by a further war with the Narzids (nomads from Chadatar who had conquered Cureia) which lasted some sixty years before simply petering out due to a lack of interest on the Narzid side. The ravaged Mafreti peninsula was then invaded from the north by a rather marginal Achaunese-speaking state led by an exceptional young king of great military talent. Açirnu of Jalīda conquered the whole of the Mafreti peninsula, the Laida Valley in Mailona and Cureia. And then he died abruptly, leaving a lot of people looking at each other in a very hostile manner.

The soil of the Mafreti peninsula had never really recovered from the deforestation crisis almost seven centuries previously. Now, exhausted by all the fighting and facing the prospect of starvation, Achaunese society simply collapsed. Famine, war and hysteria stalked the land. Roving death-priests snatched anyone they could find to appease the gods. Traditionally, the end of Achaunese civilisation is dated to 253, when the priests of Yariṣa offered every single inhabitant of their city in sacrifice to the gods and then burnt the city down when no divine bounty was forthcoming.

Two major outcomes of the fall of the Achaunese: on the one hand, the disruption to trade led to widespread unrest in the Spice Islands, but no real fall in population - the ecological collapse of the Mafreti peninsula had been strictly local in scope - which led to far more internecine conflict. Society as a result became more militaristic and stratified: it is from this time that we can date the emergence of the Impar caste system. On the other hand, crisis creates opportunity, and into the power vacuum left by the Achaunese we see the rise of two cities who would dominate the politics of the region for the next five centuries: Phareitus at the southern tip of the Mafreti peninsula, and Tailanis in the valley of the Arrosa in Mailona.

çe-ṁ-ˈbā-ra. However,

çe-ṁ-ˈbā-ra. However,  yi-ṁ-ˈbā-ra or

yi-ṁ-ˈbā-ra or  ī-ṁ-ˈbā-ra are far from uncommon (indeed the last is probably the most commonly encountered on Paríf and its surrounding islands.

ī-ṁ-ˈbā-ra are far from uncommon (indeed the last is probably the most commonly encountered on Paríf and its surrounding islands.