Yes. I am also into the wave model, which IMHO describes language families such as Indo-European better than the family tree model. Such language families start as expanding dialect continua, in which innovations spread from various centres, resulting in intersecting isoglosses, until the continuum breaks up into different languages. We see such intersecting isoglosses in IE; for instance, Germanic shares some features with Italic and Celtic and others with Balto-Slavic, which in turn shares other features with Indo-Iranian, and Greek completes the circle by sharing some features with Indo-Iranian and others with Italic.bradrn wrote: ↑Tue Jun 04, 2024 3:38 pmIn fact the tree model is pretty bad, in general. François has a nice preprint which goes into considerable detail about why and how. I strongly recommend that Talskubilos read it, in order to understand how historical linguistics actually works.Zju wrote: ↑Tue Jun 04, 2024 3:21 pmIf only there were hundreds years worth of linguistic research - done by dozens of linguists - which establishes and ascertains the tree model for the IE family...From my own research, I've found out the classical genealogical tree isn't an adequate model for the IE family,

The difficulty of subgrouping in IE is due to the rapid expansion of the family in the 3rd millennium BC. In 3000 BC, it is limited to the Pontic Steppe (already a rather large area - it is about 2,000 km from the Danube to the Ural - so there will have been different dialects); 1000 years later, it extends all the way from the Atlantic seaboard to the Hindukush.

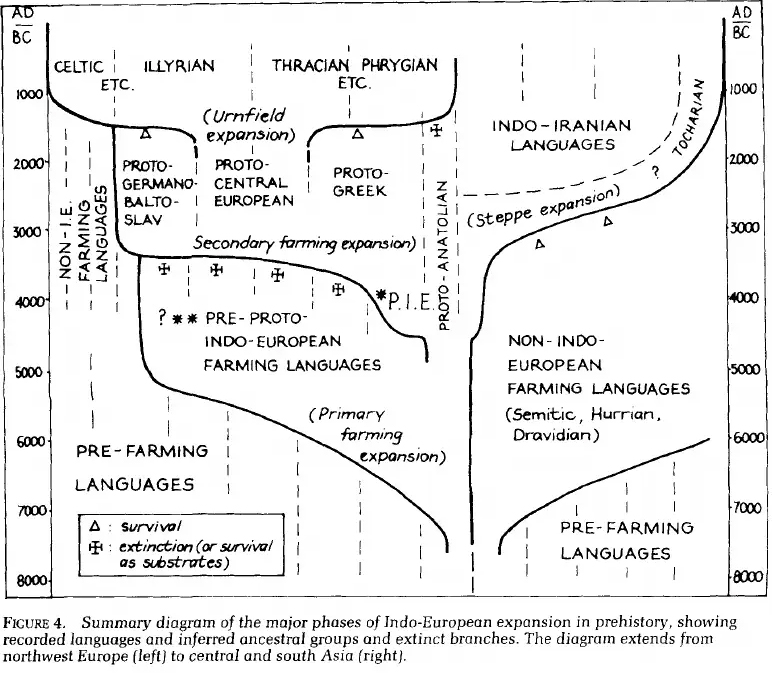

I know that chart, it is from the book Economy and Society in Prehistoric Europe by Andrew Sherratt (1997). It has partly been obsoleted by archaeogenetics (the Neolithic farmers of Europe were genetically quite different from the Indo-Europeans, originated in a different region and probably spoke languages unrelated to IE), and it does not corroborate your thinking about the IE family.Talskubilos wrote: ↑Wed Jun 05, 2024 4:08 amSurely, I didn't mean these protolanguages lasted for so long, but the whole process which ultimately lead to the historical IE languages. This would be a series of successive expansions (= waves) which replaced the previous one. An example of this idea will be this diagram (not mine):

And as for keenir's question: "Protolanguage" as used in this discussion is not a language type, it only describes the role of a language as the common ancestor of a family of languages. keenir may have confused this with a different sense the word is used in language origins studies, where it refers to a not yet fully evolved language spoken by early hominins - in times much more remote than what we are talking about here. But I may have misunderstood him, in which case I apologize.

Surely, the languages of the Neolithic farmers and the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers did not disappear without trace, but left substratum loanwords in the IE languages that replaced them, the same way Romance languages contain loanwords from pre-Roman languages of Western Europe such as Gaulish. No Indo-Europeanist worth his stripes denies this! But the largest part of the lexicon and the grammatical framework of the IE languages can be traced back to a single ancestor language - PIE.Talskubilos wrote: ↑Wed Jun 05, 2024 4:08 amIf I understood well, you refer to the number of protolanguages involved and their relationship to the historical IE languages. Although I still think this is a simplification, the late Spanish Indoeuropeist Rodríguez Adrados, who studied IE morpohology, proposed 3: PIE II for Anatolian alone, PIE III A for the Indo-Greek group (Indo-Iranian, Greek, Phyrgian and Armenian), and PIE III B for NW IE European (Celtic, Italic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic) plus Tocharian.

But in my IMHO these would be the more recent expansions, because at lexical level, there're remnants of the languages spoken by Neolithic farmers and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, which weren't necessarily related to the later ones.